Rescuing Languages from the Brink – Restoring Culture and Meaning

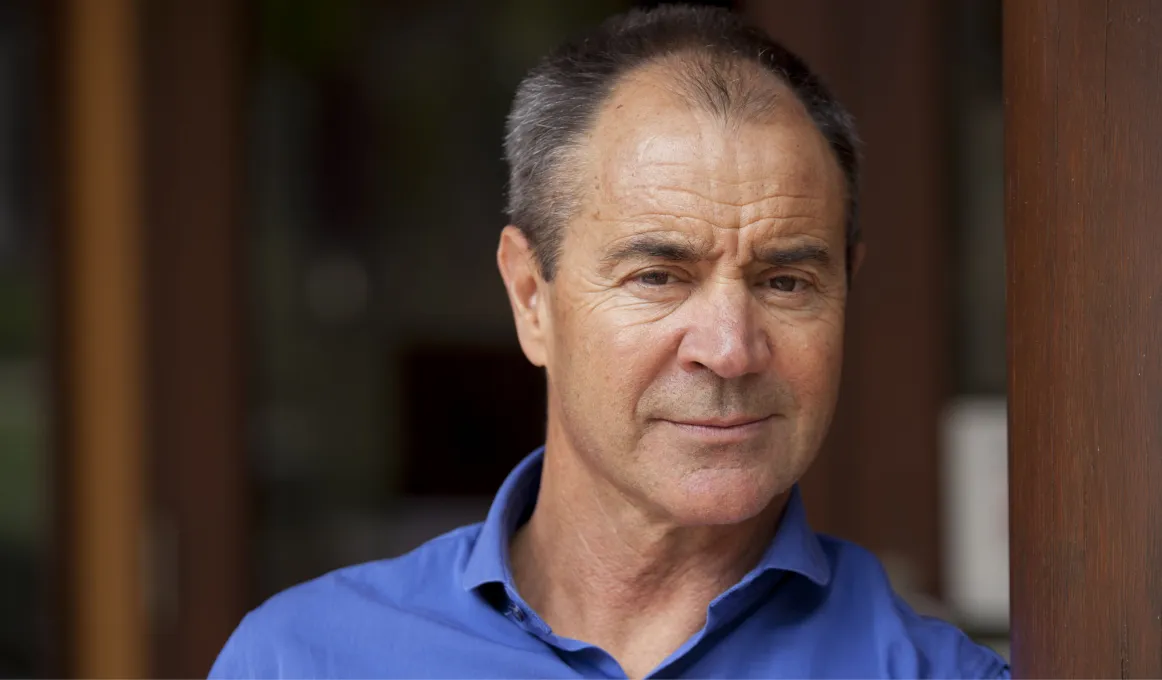

A conference will be held at the National Library of Australia in February 2019 titled: Language Keepers: Preserving Indigenous Languages. Professor Kim Scott from WA will speak the impact of language on identity and connection with place.

The sands of the beach that stretch to the waters at the tip of Western Australia can be uniquely described by the Noongar language, which finds its roots deep in the history of the land. It is the Indigenous language of south-west WA, which had been slipping into extinction but has been revitalised by efforts such as those of the Wirlomin Noongar Language and Stories project.

Professor Kim Scott of Curtin University, who has been part of the project, will speak at a National Library of Australia conference in February about the progress that has been made.

‘Our dialect of the Noongar language belongs so deeply to the southern coastline,’ he said. ‘Indigenous languages give you a different sense of being in a place and belonging.

‘Much like Latin or Sanskrit – it teaches you not just the language – but a different way of seeing the world. That same quality is inherent in all Aboriginal languages.’

The National Library of Australia conference, named Language Keepers: Preserving Indigenous Languages, will be held from February 9-10. It will be the first event presented by the Library in association with the 2019 International Year of Indigenous Languages.

Professor Scott said there were many benefits to reclaiming endangered languages. ‘It is important to confront the losses, look at the reasons for those losses and the business of people getting together to recover those languages and sharing them with the wider community,’ he said.

‘It gives us something else than just a narrative of victimhood and conquest and that’s why people talk about healing so often during conversations about revitalising languages. Recovering our language also brings a sense of identity and belonging and connection to the place you are living.

‘Indigenous languages can be very helpful in understanding the landscape and describing the things around you.’

Professor Scott said the Wirlomin Noongar Language and Stories project was a community-based language and song revitalisation collective that was formalised more than 10 years ago.

‘It has led to picture books being published in the language which revitalises not only the language but the stories of the Noongar culture,’ he said.

‘The Noongar language is endangered but in some ways everybody here speaks it because of the place names in the area.

‘Saving languages is an ongoing process.’

Find out more

Visit the National Library of Australia - Language Keepers Preserving Indigenous Languages. See more information here about the 2019 International Year of Indigenous Languages.